Today’s post is by author Amy L. Bernstein (@amylbernstein).

Driving along the back roads of Vermont, you learn to appreciate the nearly forgotten charms of the printed roadmap. GPS is spotty in Vermont, and it’s easy to find yourself on a narrow, deeply rutted dirt road that seems to lead nowhere. You get to a place where you literally can’t see the forest for the trees. And then you know you are well and truly lost.

Contemplating what comes after you’ve completed the first draft of a novel is a lot like getting lost in Vermont. The journey up to now has been beautiful and inspiring, but at some point, you have to admit that you have no idea where you’re going or if you’ll ever find your way back home.

For the writer (a traveler of sorts), this predicament raises existential questions: How do you find a way back to the beginning, or else on to the next great destination? What if you can’t decide where to go next? Why does being lost seem fun at first—and then kind of scary, even hopeless?

Getting used to getting lost

Many new writers working on a first novel never make it past a first draft—not because they’ve stopped believing in their story or because they’re lazy. They grind to a halt at the very first “The End” because they don’t know what comes next. There is no obvious inciting incident for rewrites and revisions. A great big question—How do I make this better?—often goes unanswered.

Experienced writers, on the other hand, know that their first draft is never their last draft. They know, too, that getting at least a little bit lost between drafts is par for the course. But that doesn’t mean the post-first-draft transition is easy. As in Vermont, where tiny roads branch off in all directions, figuring out which direction to head as you move from first draft to second can be a head-scratcher for novice and experienced writers alike.

Figuring out how to get from “shoveling sand into a box,” as Shannon Hale calls the first draft, to something polished enough to pitch, is not easy even for best-selling authors.

Novelist Jennifer Egan likes her first drafts to be “blind, unconscious, messy efforts.” It’s a long way from there to her polished, deeply researched books. The magic doesn’t happen overnight. John Irving admits to writing first drafts in a matter of weeks, but then spends months or years revising.

Obviously, there is no magical treasure map that every writer can follow. And even if you think you’ve found the right map for your journey, how do you know if your sense of direction is any good?

First drafts are often private affairs, the pages lying in a hermetically sealed vault, away from prying eyes. As Terry Pratchett famously said, the first draft is about you telling yourself the story. How, then, do you gain sufficient critical distance to revise your own work?

Toni Morrison flagged that challenge for all of us. “[Y]ou have to be able to read what you write critically. … [and] surrender to it and know the problems and not get all fraught,” she said.

Alas, we are not all Toni Morrison-level geniuses.

Asking the right questions

I believe we can inject a modicum of sanity into the second-draft process by focusing on universal elements of storytelling that help a writer to set priorities and to answer, at least in part, the “How do I make this better?” question.

This effort begins by focusing on five critical aspects found in most novels. A writer who systematically and honestly checks in on how each aspect functions in her novel—and identifies where rewrites and revisions are needed scene by scene to make these elements work better and harder in service to the story—is on the way to structuring a better draft.

Two big caveats before continuing:

- I’m generally referring to mainstream genre and commercial fiction, rather than deeply literary or experimental fiction, where breaking conventional rules of storytelling is expected.

- Expectations for what a second draft should achieve vary by writer. I’ll impose my bias here: I believe a second draft can and should do a lot of heavy lifting. The whole point of the virgin revision process is to make the story and its characters deeper, richer, and sharper. This is not the draft to be tinkering at the margins.

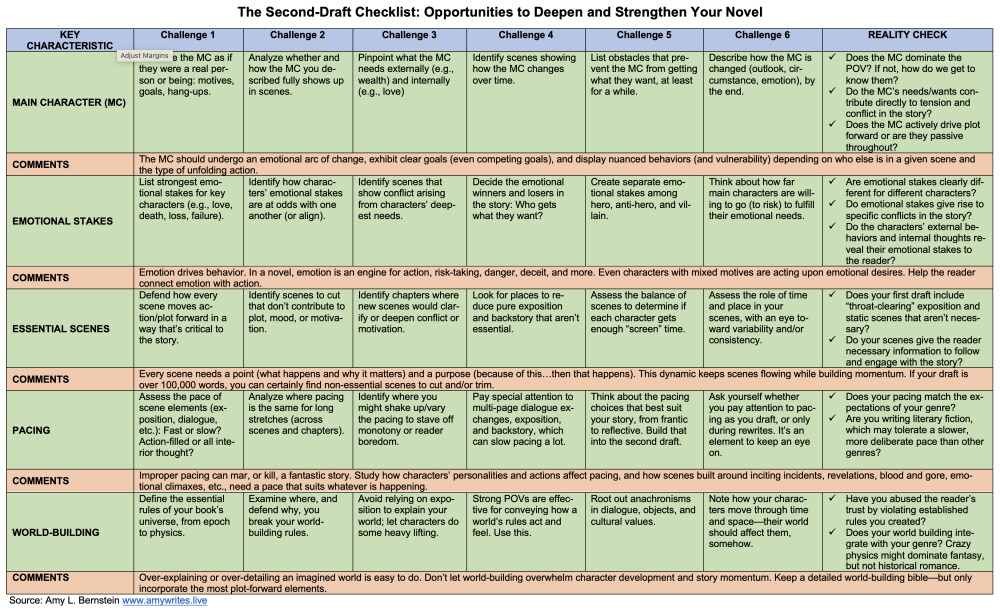

The second-draft checklist

The building blocks of the second-draft revision process are grounded in these five aspects of the novel, which stand alone and also interact with and affect one another:

- The main character (MC). The MC must be fully present in the novel: sharply drawn, replete with contradictions, a catalyst for action, and gives the reader a reason to care.

- Emotional stakes. The stakes should be high, clearly differentiated among the major characters, and serve as a source of tension and conflict.

- Essential scenes. The goal is to (a) identify scenes ripe for cutting or trimming because they don’t move the story forward or serve as static info dumps; and (b) detect where new scenes are needed to deepen a character’s motivations, reveal conflict, or add other critical texture.

- Pacing. A novel that unfolds at just one speed (all fast, all slow) is bound to bore or exhaust the reader. Variable pacing among scenes and between chapters is essential.

- World-building. World-building isn’t only for fantasy, sci-fi, and historical fiction. Every novel is built on rules, and the writer must ensure the rules are consistently applied and sufficiently sketched.

While these five building blocks are not definitive, any writer struggling to figure out what to do with their completed first draft needs to start fresh somewhere. This checklist will, at the very least, send you out along new byways, where you will make fresh discoveries about what you’re trying to say.

The key to making this checklist work for you is to work it hard: Study how each aspect functions on its own in your novel and how they work together to generate conflict, suspense, or whatever big flavors your novel needs to really sing.

Congratulations, by the way, on completing your first draft. Now get to work.

Amy L. Bernstein has worked with three traditional publishers who believed in her unagented work. Her latest nonfiction book, Wrangling the Doubt Monster: Fighting Fears, Finding Inspiration, is due out in September from Bancroft Press. Learn more here.

I need a class to help me through this exact point in my writing!

The timing for this blog couldn’t be better for me. Thank you so much for your valuable input. I’ve taken notes and I’m ready to get to work ????????