This article first appeared in Jane’s paid newsletter, The Hot Sheet.

Imprints have long been getting closed, merged, reorganized, and reborn over publishing’s history, but this summer raised new frustrations and fears among authors about how and why it’s happening. In June, Penguin Random House (PRH) announced they would merge the long-respected Razorbill into Putnam Children’s (retaining the full team in doing so); in July, HarperCollins announced the closure of Inkyard and the layoff of Inkyard’s staff. Harlequin Teen (started in 2009) was relaunched as Inkyard in 2019, publishing both YA and middle-grade fiction.

We talked to three industry experts about what prompts imprint closures and what authors should expect if they find their imprint on the chopping block.

The most straightforward explanation for imprint closures: lack of sufficient sales. It’s only logical: Publishing is a business, and if the imprint doesn’t earn its keep, there’s only so long it can continue. “Publishing companies today look at imprints through the cold calculus of earnings,” says Paul Bogaards, a longtime Knopf exec who now runs Bogaards Public Relations. “The consolidation that is taking place across the industry—and the closure of imprints—is principally tied to economics.” He says that business managers across the publishing industry review yearly profit & loss statements, and if an imprint is consistently in the red, watch out.

Publicist Kathleen Schmidt, who has had a long career in traditional publishing, agrees. “If the acquiring editors of the imprint are bringing in projects that aren’t selling well enough as frontlist titles, chances are they will not backlist well. While there isn’t a specific frontlist sales number associated with being a profitable backlist title, publishers often know, based on similar books, which ones have the ability to sell steadily over time. If an imprint isn’t producing titles that will add to a publisher’s backlist, it becomes a liability. Additionally, if an imprint’s frontlist titles continue declining sales rather than remain steady or become profitable, it makes more fiscal sense to fold the imprint into an existing one. Often, when this occurs, the staff at the imprint being shuttered is let go.”

In the case of Razorbill and Inkyard, it helps to consider current sales trends: The children’s market has been declining. In 2022, children’s hardcover sales were down 12.5% versus the prior year and below their levels from 2020 and 2019. Circana BookScan reports that frontlist children’s hardcover sales fell more than 20% last year. Additionally, Barnes & Noble has been reluctant to stock children’s middle-grade hardcovers because they are often returned unsold to publishers.

Schmidt says, “Over the past two to three years, B&N has skipped buying many titles because they are no longer willing to take as many chances on debut authors and are being conservative with numbers on previously published authors with mediocre sell-through. Further, B&N store managers aren’t overstocking categories. The cuts in children’s titles are a good example of this. In the YA category, BookTok plays a big part in what B&N carries. Independent bookstores only account for a small percentage of book sales. Amazon is truly where sales are concentrated right now, and though they stock pretty much everything, it doesn’t mean it sells. Discoverability is a major issue there.”

Andrea DeWerd, who runs The Future of Agency and has worked in marketing and publicity at three of the Big Five publishers, says that sometimes imprints spend too much on acquiring books, and “the sales simply aren’t there” to back up big advances. She sees that as more of a risk with personality-driven publishing, where an important editor is given their own imprint due to connections or relationships that bring in high-profile projects (and often high expenses). While imprint closures can appear sudden, she says once you look back, you can often see the signs that it wasn’t working.

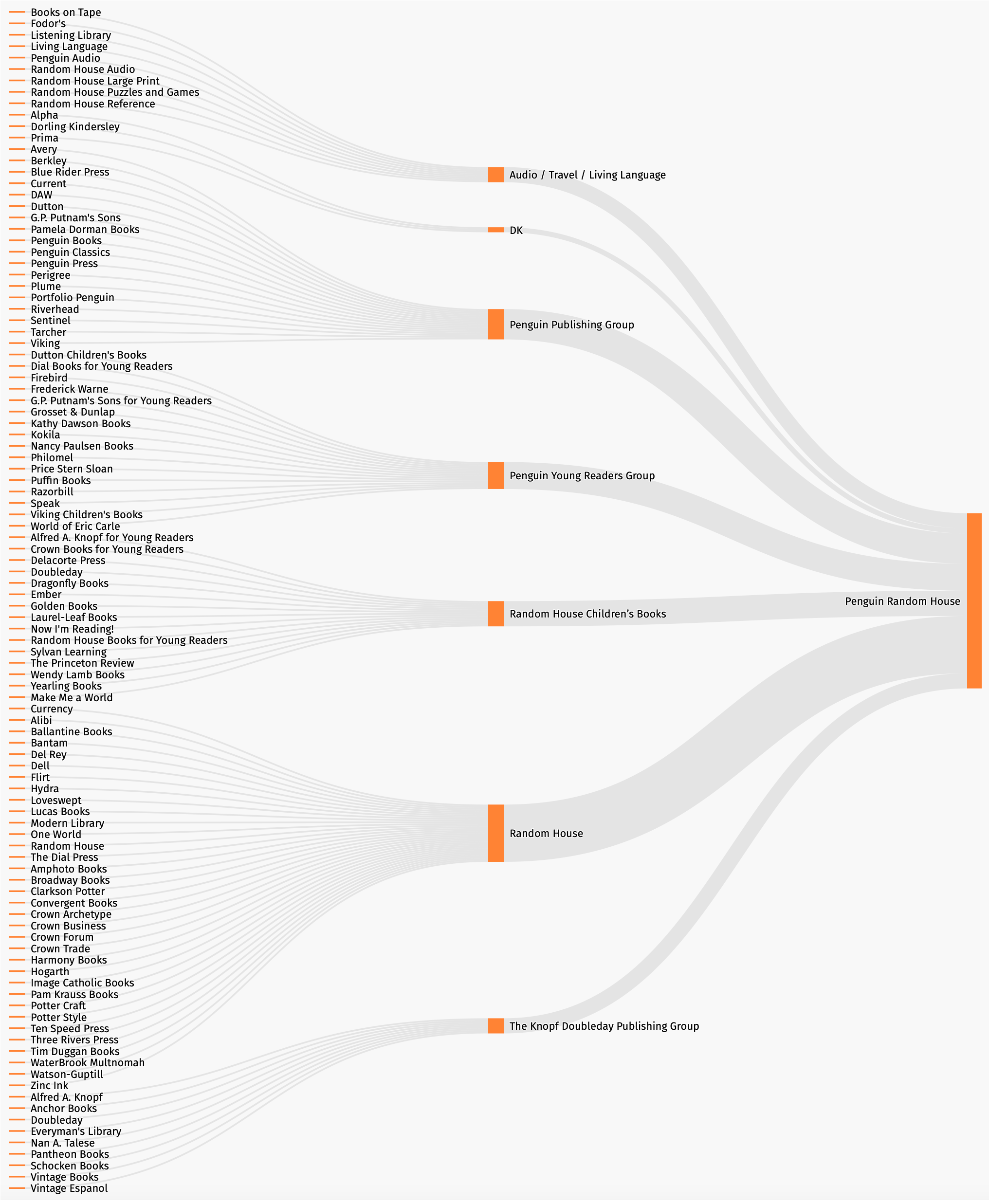

Some imprint launches are opportunistic, meant to take advantage of current events or a growing market. Because of the socio-political situation today, you can see this as clearly as ever: Since 2016, new publishers and imprints have appeared to serve the conservative and far-right political audience. Alongside those are an increased number of imprints focused on BIPOC authors and historically underrepresented voices. One publishing industry veteran wondered why publishers start so many imprints in the first place (see imprint map below for a visual), and suggested that it’s partly about sending a signal to certain buying or marketing communities. Obviously sending a signal doesn’t always come with a viable business model, and when the market opportunity passes—or when the economic environment gets challenging, as it is right now, with everyone in cost-cutting mode—such efforts are the first to go.

Are publishers being patient enough to see new imprints pay off? It depends on who you ask, of course. Bogaards says publishing used to be a more patient business, which was a saving grace for both editors and imprints alike. Despite that, he says, “[Publishers] still believe in the acquisitions they are making. They are, however, being thrifty with post-acquisition spend, and writers need to understand this. Writers need to be thinking about what critical investments they should be making in their work. In the old days, you could leave it all to the publishing house. And for a select subset of authors, this may still be true. But many writers will benefit from learning about, and then making, publication investments/spends.”

And a warning for authors who unfortunately signed with an imprint that’s been closed: DeWerd says it can be very challenging to continue to sell through or publish through the imprint’s schedule of titles when it no longer exists, because even though marketing and publicity staff still work on those titles, they don’t necessarily have a clear point person to go to for important decisions or budget approval. And that can be to the serious detriment of those books. She says authors shouldn’t take at face value a publisher’s claim that nothing is going to change when an imprint shutters.

When imprints close or merge, sometimes it’s about personalities and power in addition to efficiencies. PRH recently laid off legendary editors at legendary imprints, which has led to a great deal of pessimism about the state of book publishing. While Bogaards believes that “emotional ties to imprints are relics of a bygone era,” sometimes these moves are about “clipping wings,” because corporate leadership doesn’t want to deal with a power base that lives outside of it. “Sonny Mehta [at Knopf] was a headache for years!” Bogaards says. “He ran a profitable imprint, and when the corporation wanted to rein him in, he told them to ‘f— off,’ and they did. The numbers kept the corporate tinkerers at bay. When he died, all that changed. Profits were down, so they were waiting in the wings. They got in there with their scalpels and started taking imprint jobs and amortizing them into divisional jobs and then into corporate jobs—because it was cost-efficient to do so. Does a publishing company need a head of production for every imprint? A managing editor? An art director? A marketing director? The answer, as it turns out, is no.” (And indeed, a day after Bogaards made this point, mid-size publisher Abrams announced structural changes that impose such efficiencies.)

DeWerd says that the people in leadership or finance always have their eye on potential and immediate solutions to make budget, and sometimes imprint closures may come down to cutting very senior people making high-level salaries. (Typically, these are people who hold titles such as editorial director or publisher.)

Ultimately, neither how well an imprint once did nor its long-standing reputation offers indefinite protection. Schmidt says, “If an imprint has a robust backlist but the editors who acquired those titles haven’t acquired anything profitable in a long time, it is easy for a new CEO to eliminate those salaries. You don’t need the editors to continue backlist sales, because there is a department dedicated to doing so (sales/marketing).” Case in point: This year, McGraw-Hill stopped acquiring new business titles but has held onto its backlist.

Bottom line: Bogaards says, “The majority of readers have no idea who published their book. Many media outlets have given up identifying imprints in their coverage of books.” And DeWerd said that the imprint’s name or reputation doesn’t necessarily affect how the sales and marketing team positions or talks about forthcoming books. Most often the imprint is a neutral factor, whereas the sales rep’s relationship with their account can matter much more, she says.

In the end, it may not matter which imprints stay or go as far as the fortunes of authors or the future of book sales. And for a slight bit of encouragement: “The focus on data and the need for books to be profitable has not winnowed what is being published in an appreciable way,” Bogaards says. “The opportunities for writers are still there. That’s not to say it won’t thin down the road. It may well.”

If you enjoyed this article, consider a subscription to The Hot Sheet, brought to you by Jane Friedman.

Jane Friedman has spent nearly 25 years working in the book publishing industry, with a focus on author education and trend reporting. She is the editor of The Hot Sheet, the essential publishing industry newsletter for authors, and was named Publishing Commentator of the Year by Digital Book World in 2023. Her latest book is The Business of Being a Writer (University of Chicago Press), which received a starred review from Library Journal. In addition to serving on grant panels for the National Endowment for the Arts and the Creative Work Fund, she works with organizations such as The Authors Guild to bring transparency to the business of publishing.

Great info! Thanks so much!